Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'opentype'.

-

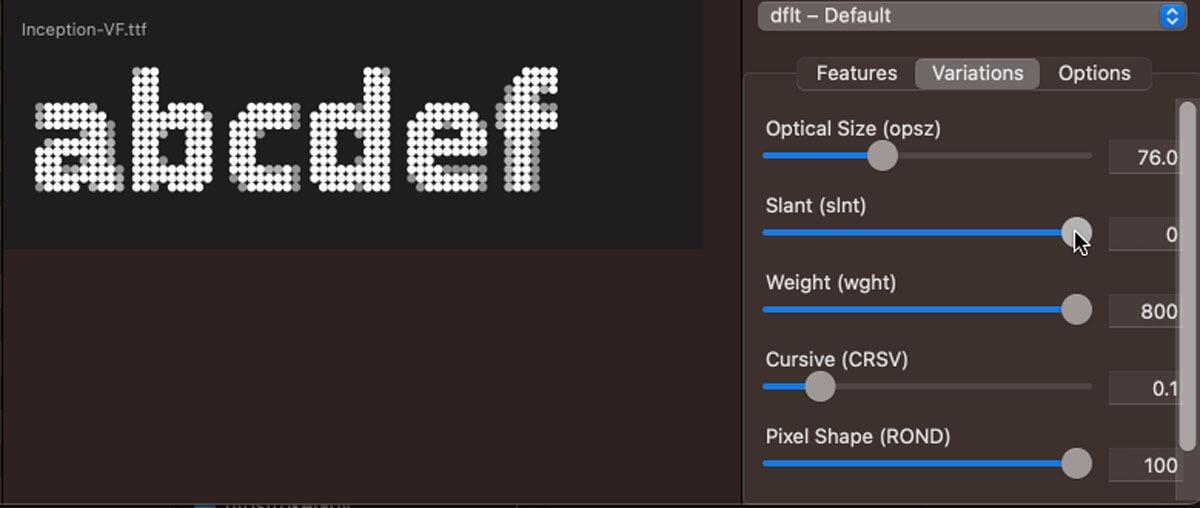

Access OpenType features with Apple’s font panel

Ralf Herrmann posted an academy lesson in Typography on Apple devices

-

-

- video

- postscript

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

… a playground with samples for the most common OpenType features available out in web typography. You can have fun toggling each feature individually to see its effect in action.

-

- opentype

- web typography

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

-

MetricsMachine is a commercial kerning app for Mac OS X developed by Tal Leming (TypeSupply). MetricsMachine is streamlined for a professional workflow: you create groups of similarly shaped glyphs, then you create lists of pairs that you want to proof, then you proof those pairs one at a time until you are finished, then you export your kerning to an OpenType ready feature file.

-

First of all, it’s important to know that OpenType is not as new as some marketing claims try to suggest. It is directly based on the TrueType specifications, or to be even more precise: it is based on Apple’s SFNT (“Spline Font”) format originally developed for QuickDraw. You can think of OpenType as “TrueType 1.5”. It uses the same basic structure as a TrueType font, but with some optional features stored in additional tables within the font. Which brings us to our first myth: OpenType brought cross-platform compatibility Wrong! Until MacOS 9 both TrueType and PostScript Type1 fonts had to be delivered as separated versions for PC and Mac. This was in large parts due to the way Apple stored font information in the resource fork of a file. Since MacOS 10 the new Mac operating system also supports data fork fonts, such as Windows TrueType fonts. So platform compatibility was made possible by this change from Apple, not by the introduction of a new font format. But since OpenType is directly based on the file structure of a (Windows) TrueType font, OpenType is also cross-platform compatible. OpenType fonts have a larger character set Just partly true. The old PostScript Type1 fonts usually had just an 8 bit encoding like Mac Roman, which only allowed to address 256 characters. This made setting different languages or writing systems a pain. Different font files of the same typeface (like Helvetica CE/Greek/CYR) had to be used in one document and without these fonts installed the text could not be displayed properly. OpenType with its Unicode support clearly solved this dilemma, but then again: this was not something that was developed specifically for OpenType. The older TrueType fonts also supported Unicode and larger character sets. What OpenType really introduced was a new way to access these larger character sets. Instead of just accessing them via their Unicode, they can now be accessed using OpenType features, like the LIGA feature, which (for example) automatically replaces every instance of f and i with an fi-ligature. Or the AALT feature which allows you to access all alternative versions of a glyph in the Glyph Palette of InDesign. But then again: Having an OpenType font doesn’t mean that all those features and extended character sets are really there. You can turn a TrueType font into an OpenType font by just adding one fi-ligature as an OpenType feature. So as you can see: Drawing a strict line between TrueType and OpenType as two separate formats often doesn’t make any sense at all. Often people ask, how they can convert old TrueType fonts to OpenType. But this would be completely pointless since there is nothing to gain from such a conversion, unless the font foundry itself decides to really add additional glyphs and features. OpenType is more reliable, compatible and better supported than TrueType Wrong! Users often think they should generally prefer OpenType over TrueType, mainly because of the bad reputation the TrueType format still has. But this is a myth of its own. It comes from the early 1990s when “professional” fonts were usually PostScript Type1 only and thousands of TrueType fonts of poor quality were used by semi-professionals and such fonts caused problems with the Raster Image Processors when used in print. But these days are long gone. Today there is no reason to avoid TrueType fonts anymore and as I have explained before, a TrueType font and an OpenType font can be almost identical. OpenType is not even more compatible, as some users like to think. Since OpenType is a superset of TrueType, whenever there is OpenType support, there is also TrueType support. OpenType fonts render badly in Windows Depends! I heard this myth a lot recently in all this talk about webfonts. What is really meant here is that PostScript outlines may look bad in Windows, because they might be shown without subpixel rendering (ClearType). It is very important to know that an OpenType font might be either TrueType-flavoured or PostScript-flavoured. TrueType outlines use quadratic Bézier splines and PostScript outlines use cubic Bézier splines. So if we want talk about the outlines of a font, using the term OpenType alone makes no sense at all! We already established that a TrueType-flavoured OpenType font is like a TrueType font with some optional OpenType features. A PostScript-flavoured OpenType font is the same thing, but the part that defines the TrueType outlines (the “glyf table”) is here replaced by a “CFF table” (Compact File Format). That’s why PostScript-flavoured OpenType fonts are also sometimes called CFF-based OpenType fonts. So if the outline format matters it is really recommended to speak of TrueType- or PostScript-flavoured OpenType fonts. Common abbreviations are OpenType TT and OpenType PS. So, TrueType fonts use .ttf and OpenType fonts use .otf, right? Wrong! Unfortunately, the suffix doesn’t tell you for sure what you have. OTF is mostly used for PostScript-flavoured OpenType fonts, but according to the OpenType specifications TrueType-flavoured OpenType fonts can also use .otf. TTF on the other hand is both used for regular TrueType fonts and for TrueType-flavoured OpenType fonts. This makes sense, since as we have learned before, these types of fonts are pretty similar. By keeping the old TTF file extension TrueType-flavoured OpenType fonts can work in older apps and operating systems that have no specific OpenType support. The fonts are then treated as regular TrueType fonts and the OpenType features are simply ignored. But I can tell the font format from the icon, right? Wrong! If you look into the font folder of a Windows XP or Vista installation you see some fonts with an OpenType icon and some fonts with a TrueType icon. Again, these will not tell you for sure, what type of font you have. PostScript-flavoured OpenType fonts will have the OpenType icon, but it gets complicated for TrueType fonts. Microsoft decided to base the icon on the existence of a digital signature which was also introduced in the OpenType specifications. This means, TrueType-flavoured OpenType fonts might have an OpenType icon (if they have a signature) or they just might look like a regular TrueType font (if they don’t have a signature). Windows users might install the Font Properties Extensions which will give more detailed information about the installed fonts, including the OpenType features of OpenType fonts. But OTF means “OpenType Font”, right? Well, … While it is true that OTF means OpenType Font, I generally advise people not to use the abbreviation OTF when one wants to talk about OpenType fonts in general. OTF is usually (but not necessarily) the file extension of a PostScript-flavoured OpenType font, so if one talks about “OTF fonts” it’s not really clear if this should exclude TrueType-flavoured OpenType fonts or not. I recommend to speak of “OT Fonts” for OpenType fonts in general and “OpenType TT” and “OpenType PS” if the outline format matters.