Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'eszett'.

-

The Multifaceted Design of the Lowercase Sharp S (ß)

Ralf Herrmann posted a journal article in Journal

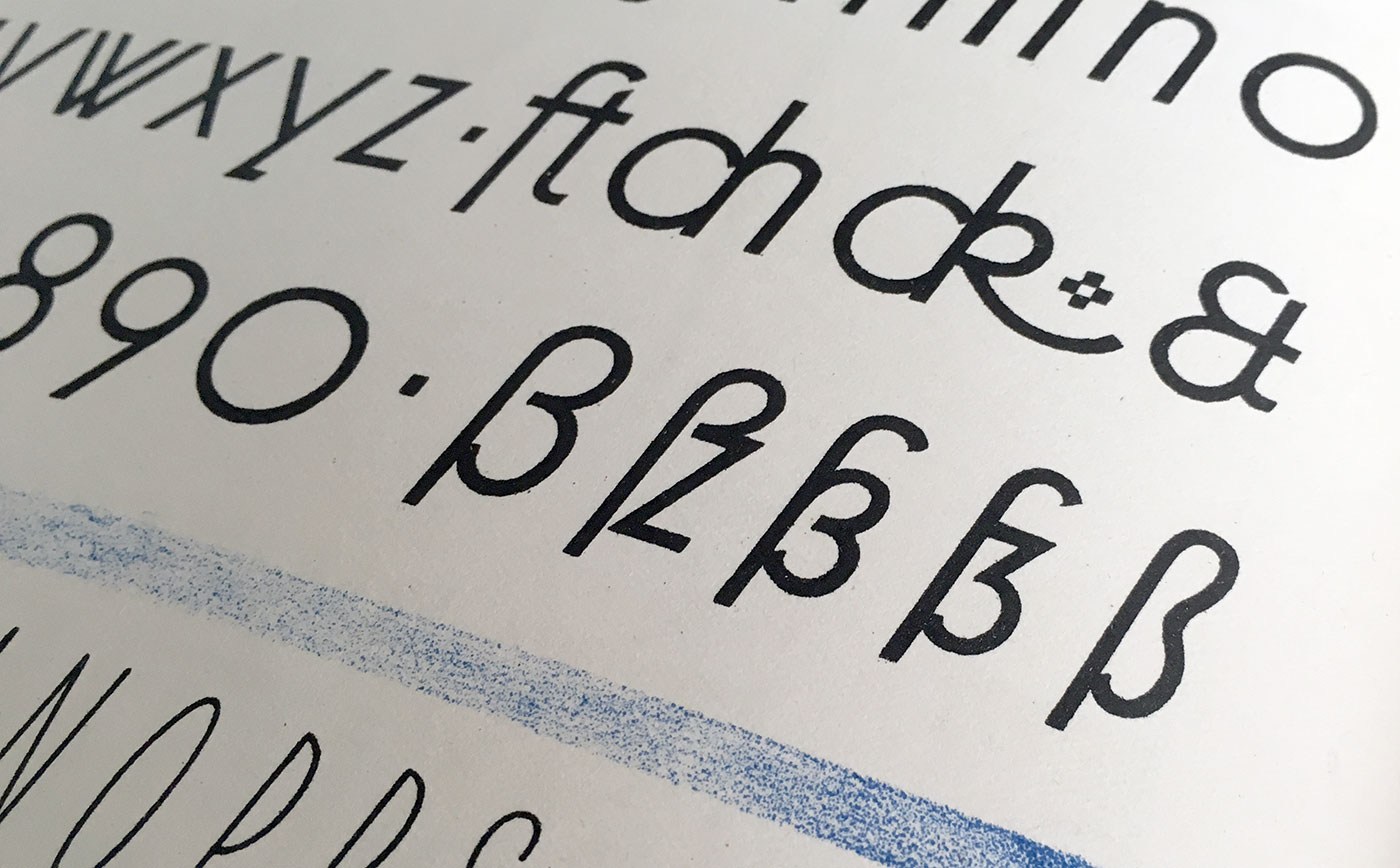

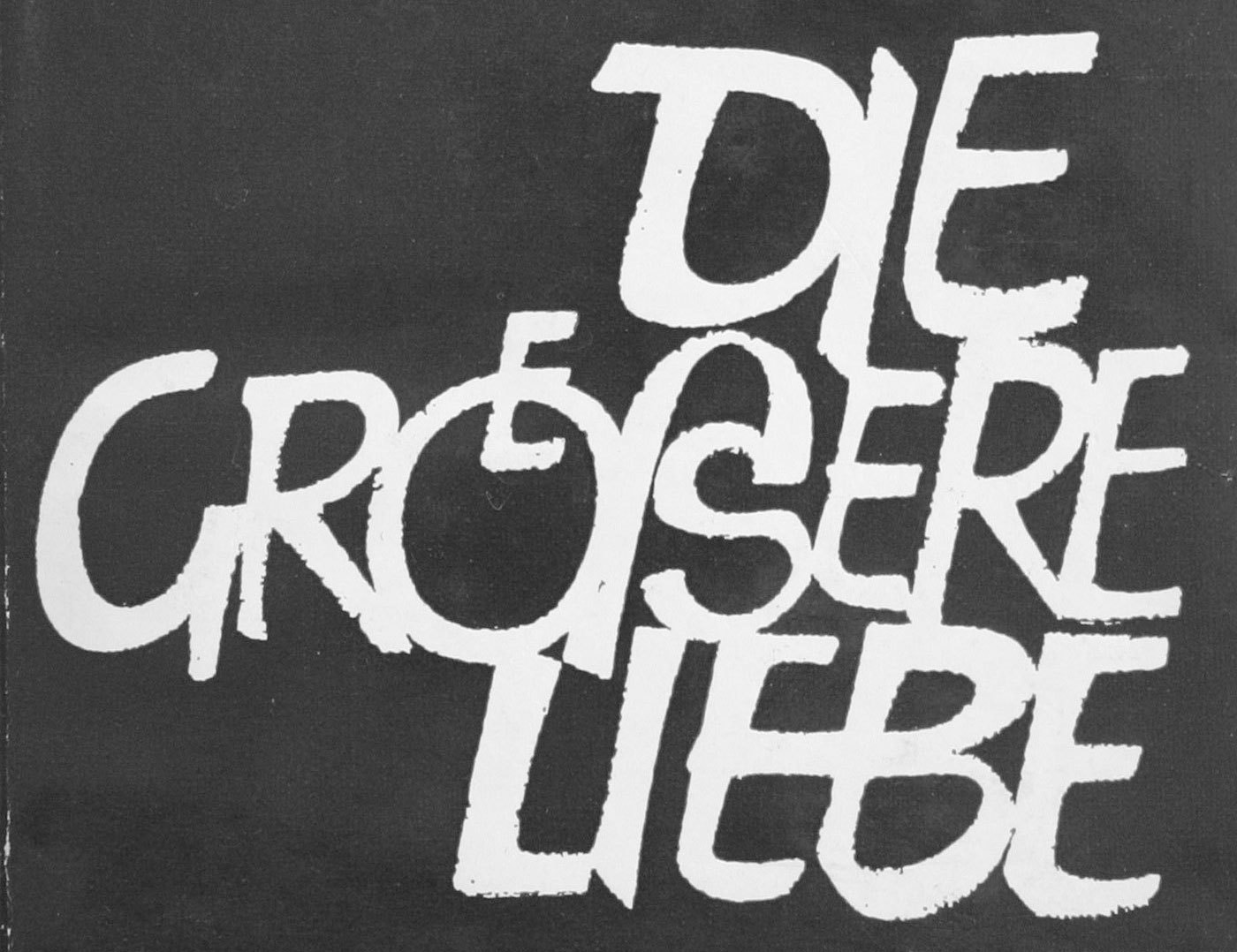

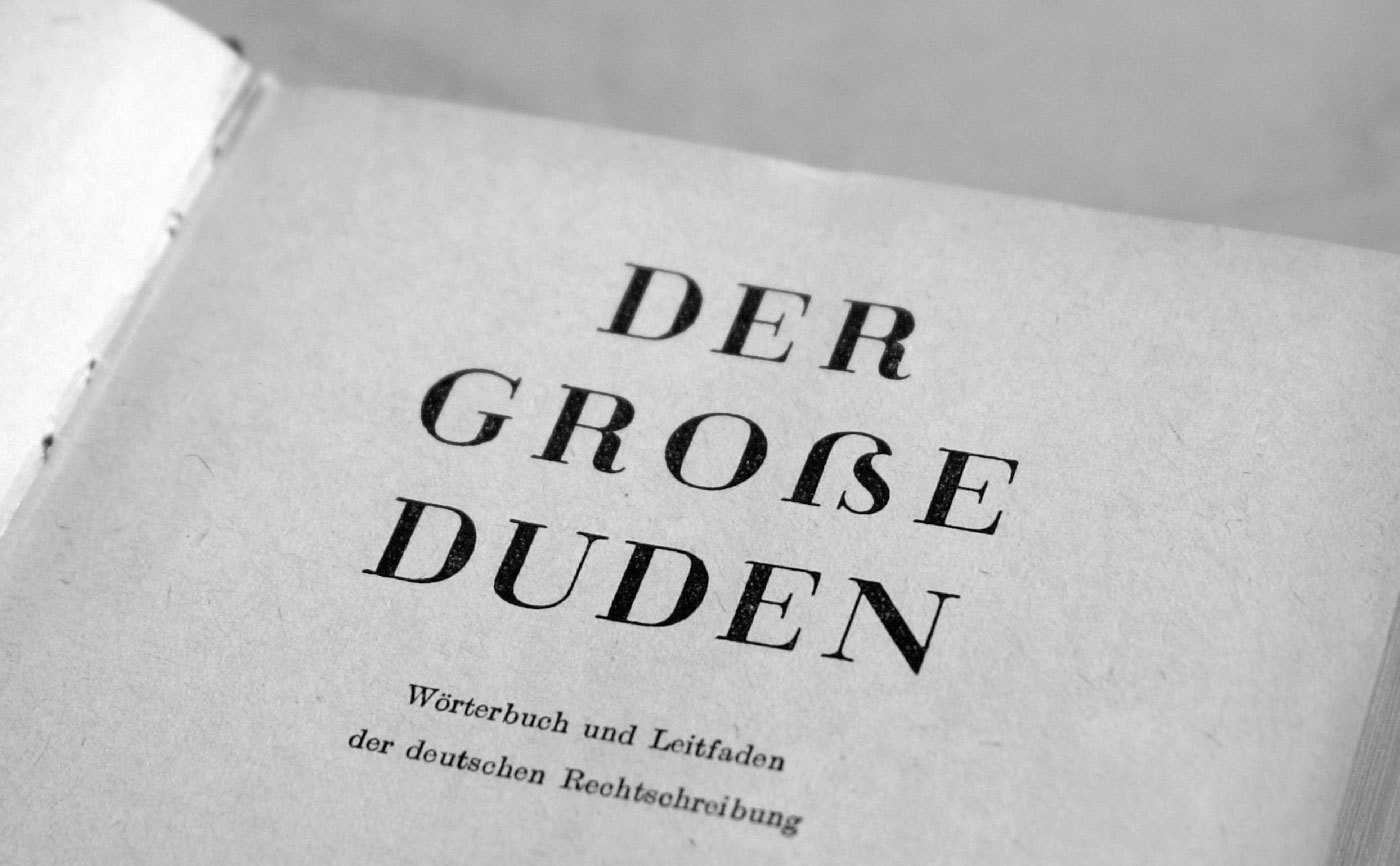

The sharp s (or “Eszett” as it is called in German) is a letter of the alphabet in Germany and Austria. The Unicode casing rules state: “The German es-zed is special”. Indeed it is! Its (still not fully explained) history is full of twists and today’s understanding of this history is often full of misunderstandings. The origins of this character won’t be the discussed in detail in this article. Instead I will focus on the stylistic options which have resulted from the recent history. Sharp s variations for an alphabet in a lettering/calligraphy book from the 1930s by Willy Schumann Today there are two standard models for the design of the ß character. They are explained at first and are recommendable for most of today’s typefaces. 1. The ſs Ligature Design This design is both very old and rather new at the same time. It was used for centuries across Europe, especially in cursive writing, either as a purely stylistic choice or in accordance with a typesetting practice which avoided a long s as the end of words and therefore displayed a double s (ſſ) as ſs, either visually connected or not. ſs ligatures from Giovanbattista Palatino, from a 1578 compendium Since this design in its connected form is so visually similar to the typical modern German ß, it is often mistaken as the actual origin of the German character. But using this design for German texts is a rather new practice, which only became typical since around the middle of the 20th century. At that time, the roman and italic type styles of the Latin script replaced blackletter and Kurrent for German texts and with that, the influence of blackletter on the design of German typefaces started to vanish. Typical German blackletter ligatures (such as ch, ck, tz) came out of use and the understanding of the ß character shifted slowly. In caps-only typesetting the ß would be set as SZ in the beginning of the 20th century, but later SS became more common and finally the only correct spelling—until the introduction of the capital sharp s. Without the influence of blackletter, a German alphabet in the roman type style was now again more clearly based on designs from the time of Classicism and Renaissance and the historic ſs ligature became a perfect fit for the German ß—both in its design and the understanding of the character. Using this ligature design is the typical choice for so-called humanistic typefaces, i.e. designs which have their roots in the traditional book typefaces of the Renaissance. Both serif and sans serif typefaces can use this design model of the sharp s character. The ſs ligature design in Optima and Syntax Designing the ß in this style is rather simple, since it really is just ſ and s connected with an arc. The connection however is mandatory today. While an unconnected design is a historic variation, it won’t be accepted by today’s readers. The upper counter area is ofter narrower than the lower counter area, as it can be seen in the examples above. But there are also typefaces with a more prominent upper counter area, especially in italic styles. The sharp s in Sabon The arc and the s shape usually connect as one continuous curve, but there are a few typefaces which stress the different letter parts more clearly by making an abrupt change of direction. This can also work fine. But just to be clear: German readers without a background in typography see the ß as one character. Stressing ſ and s as individual parts of that design is neither expected nor necessarily helpful. Just as a W exposing its origin as ligature of two V is a possibility, but not necessarily helpful. The sharp s in Utopia and Calibri The ſ in its upright version might have a horizontal stroke on the left side and the ß then gets this stroke as well. This is a traditional design feature, but not really required. In my opinion, it only supports the confusion of ſ and f and therefore the horizontal stroke might also be omitted for ſ and ß in modern typefaces. Either way, ſ and ß should always follow the same principles. And speaking of the long s: It will usually have a descender in the italic design, but not in the roman version. The same is true for the sharp s. Upright and cursive styles of Tierra Nueva. 2. The Sulzbach Design As already mentioned, German was mostly set in blackletter (or written in Kurrent) until the middle of the 20th century and the sharp s as German character was established and mandatory in these type and writing styles. When German was written or set in the roman type style, a counterpart for the blackletter ß wasn’t available for a long time. As a result we can find different alternative spellings until the end of the 19th century. For example: a word like “groß” (big) in blackletter could appear as gross, groſs or grosz in roman typefaces. German book from 1795 in a roman typeface (Prillwitz Antiqua) using ſs where a blackletter text would always use ß. Around 1900 an official German orthography was established and a committee of type founders and printers met to define rules regarding the design and use of German characters like ß, ö, ä, ü in upper and lower case. At that time, typesetting and writing German in the roman style had already gained popularity and there was a need to find solutions and regulations regarding the different practices used for blackletter and non-blackletter typesetting. Some differences were kept, some things were unified. The ſ character was kept for blackletter, but dropped for setting German in roman and italic typefaces. The ß on the other was understood as a character of its own, which had become so important, that it was decided to add it to all typefaces, not just blackletter ones as before. All German type foundries should add it to their roman and italic designs. The design proposal that was chosen had similarities with an unusual letter used in the 17th century by the printer Abraham Lichtenthaler in the city of Sulzbach and is therefore now known as “Sulzbacher Form” (Sulzbach design). Sharp s in the Sulzbach design added to Walbaum Antiqua in the 20th century. In the time of Justus Erich Walbaum such a roman typeface had no sharp s. The new design doesn’t include a clear s or z shape, but consists of a long s at the left side and two connected arcs on the right side. As a result, the letter often looks like an uppercase B to people not familiar with German. This design was applied to many German non-blackletter typefaces after 1903, including the traditional old-style and modern typefaces. It remains in use until today, but mostly for more geometric/constructed typefaces, where the simplicity of the two arcs works better than the flowing connection of the upper arc of the long s with a lowercase s. Sharp s in Futura The Sulzbach design can more easily use an upper counter area that is similar in size and as width as the lower counter area. A tear-shaped or ball-shaped terminal can be used for serif designs. The connection of the two arcs in the middle should reach to the left as far as necessary, to make the character legible, but not so far as to suggest a connection with the stem – after all, it is not a B. And of course the aperture at the bottom should not be closed. Sharp S with teardrop terminal in this version of Bodoni The Sulzbach design is also the standard model for German handwriting. It will usually be written with a descender and fonts might replicate this. Sharp s in German in the historic Kurrent handwriting Handwritten sharp s FF Schulschrift The Schulbuch typeface is aimed at children learning to read and uses the descender of the handwritten sharp s. The two models explained above should suffice to design a proper ß for almost all roman and italic typefaces, but there are more variations in existence. For the sake of completeness they are shown below. They should only be used where appropriate. An unusual design of the ß character can make a typeface unsuitable for setting German, especially when it is supposed to be used for copy texts. It’s often better to include uncommon/historic designs as stylistic alternates and put a standard ß in the default slot for this character (U+00DF). The beautiful sharp s in the metal version of Bernhard Schönschrift (1925) The unusual sharp s in Ratio-Latein (1923) Historic Variation: The “Blackletter ß” With German blackletter and non-blackletter typefaces being used side by side since the end of the 19th century, type designers also started to mix elements of the two. The sharp s in blackletter Blackletter fonts became more simplified and the letter skeletons of the early blackletter fonts became more popular, which were still closer to the design of the roman letter style. And roman typefaces from German foundries started to “look more German” in the first half of the 20th century. The mandatory ligatures of blackletter typesetting were often added to the character set of the roman typefaces and the design of individual letters was also borrowed from blackletter typefaces. A typical case for that is the sharp s character. Many, but not all typefaces used the recommended Sulzbach design. A design as a ligature of a long s with something like a 3 with a flat top resembled the typical look of a blackletter ß and also became a popular choice until the middle of the 20th century. The blackletter-inspired sharp s in Erbar Meister-Kursiv by Herbert Thannhaeuser, 1952 Technotyp by Herbert Thannhaeuser, 1948 Not using a descender is also possible for this kind of sharp s Because the “blackletter sharp s” in roman typefaces is typical for the first half of the 20th century, its use can still evoke a connection with that time. It appears—as default or stylistic alternative—in a few modern typefaces as well (e.g. FF Kava, Verlag, Metric, DIN Next Slab) and is legible within a word context, but it is not something that works for every font or use case. The examples shown above represent the most typical design of this “blackletter sharp s” approach. But as a variation, some typefaces also use a design that looks like a 3 with two arcs or a z design on the right side of the ligature. These designs might not work so well for today’s readers. The sharp s in Ehmcke Antiqua (1909), which is also in the digital versions named Carlton. The URW++ version of Bodoni While used occasionally in the 20th century—a literal Eszett (“sz”) ligature is not recommendable today. Historic Variation: The Connected Script ſs Ligature I already explained the ligature of a long s and a round s where the top part of the long s is used to make the connection to the round s. But in connected cursive writing there is also a way of writing a regular long s and then making a connection from the bottom, usually as extension of a descender loop in the long s. This style can also be found across Europe and across different languages over several centuries. It usually just represents a double s, but in a German text that isn’t written with a long s as individual character, this design represents the sharp s, as seen in the following examples. From an original type specimen booklet of Justus Erich Walbaum from the early 19th century. “daß” and “bloß” are typeset as “daſs” and “bloſs”. This design can be found in use until the 20th century, but it not common anymore and will probably confuse many of today’s readers of German. An undated German school poster shows the connected script ſs ligature as alternative to the regular ß in the Sulzbach design. -

Capital Sharp S designs. The good, the bad and the ugly.

Ralf Herrmann posted a journal article in Journal

Two years ago I wrote an article with suggestions on how to design a Capital Sharp S (ẞ). Now that over 600 new type families with support for this new character have been released, I thought it would be a good time to review, how the type designers have drawn their Capital Sharp S. At first, I present the designs I consider most successful, grouped by their design principle. There is a convention in German of naming different designs of the uppercase and lowercase Sharp S by certain cities and I am following this convention. Design “Dresden” with a an arc at the top left This is the design most typefaces use. It works like a capitalized form of the lowercase character (ß). But in contrast to the lowercase design it has a diagonal stroke at the top right in order to differentiate it from the letter B. Note how wide the character is in those examples. Designs that start from the lowercase ß can easily be too narrow, which might not be ideal among the other uppercase characters. Typeface shown above: Espinoza Nova, Henriette, Ernestine, Scotch Modern, Andron, Museo Slab Design “Dresden” with a corner at the top left In the sample shown above, the arc on the top left is derived from the lowercase letter ß. Some designers think, that such an arc doesn’t work well within the Latin uppercase letters. So, to avoid this “lowercase look”, one could draw the top left of the Capital Sharp S as a corner. This works especially well with more geometric typefaces. Typefaces shown above: Iwan Reschniev, Backstein, Hypatia Sans, LiebeRuth, Rooney Design “Leipzig” This design uses a clearly visible S as the right part of the Capital Sharp S. It works especially well with typefaces with a more calligraphic look. Very few typefaces use it, even though it is an interesting design that doesn’t cause any ambiguity problems. Typefaces shown here: FF Oneleigh, Numina, FF Fontesque Design “Zehlendorf” This is a new approach that was introduced by Martin Wenzel and Jürgen Huber within their design for the corporate typeface of the German government. They named it “Zehlendorfer Form” after the district in Berlin where their office is located. Its design falls right between “Dresdner Form” and “Leipziger Form”. It doesn’t use a diagonal stroke in the top right part, but a narrow S-like arc. The white-space and width of the character makes it very distinct. Its very legible and cannot be mistaken for a B. Conclusion Up to this point in time, the design model “Dresden” is clearly the most popular one for designing the Capital Sharp S. But I would be happy to see more of the design model “Leipzig” (third letter) and “Zehlendorf” (fourth letter) in the future. What not to do: A rounded top right segment Not all Capital Sharp S designs are convincing yet. The problem I have seen most is to stick too close to the lowercase design of ß and give the Capital Sharp S a rounded top right part. This results in something like an “ugly B”, but cannot be read easily as sharp S (ẞ). I suggest this simple test: First, cover the left side of the letter. Now check: can the remaining right side be read as a B? Then the design should be improved. What not to do: Using a double S design I have seen several typefaces which just put SS in the slot for Capital Sharp S. This is like putting two independent V in the slot for W. Yes, there might be a historic, typographic or orthographic connection, but it’s still wrong. The Unicode slot U+1E9E was created for the character Capital Sharp S. A W is not the same as VV and ẞ is not the same as SS. If you don’t like the idea of a Capital Sharp S, you better not use U+1E9E at all. But don’t put a double S in it. In the same vein, don’t try to create an uppercase SS ligature as Capital Sharp S. The whole point of the Capital sharp S is, that ß and ss represent a different pronunciation nowadays and without ẞ this difference cannot be maintained in uppercase-only typesetting. So an SS ligature doesn’t solve anything. It is just read as SS and not as a representation of the sharp S character.- 4 comments

-

- 1

-

-

- type design

- capital sharp s

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

The letter ß came into existence in German blackletter writing, where it didn’t require an uppercase counterpart, because it stood never at the beginning of words and blackletter was never set in uppercase only. But since German is set in Roman script, there is an obvious gap in the German alphabet. Proposals to fill this gap were made since the 19th century. Here are designs that were discussed at the beginning of the 20th century: A commission of German publishers, printers and type foundries introduced the lowercase ß when German was set in Roman script, but the introduction of a capital ß was postponed because the commission could not agree on a design at this point. This comes as no surprise, because it had to be created from scratch and there was nothing to base the design on and the German readers where not used to see such a new character in their alphabet. New proposals appeared in the 1950s in the German magazine Papier und Druck: Even though the capital ß never became an official part of the German orthography during the 20th century some type foundries included it in their alphabets and it appeared occasionally in print. The Capital Sharp S today Since 2008 the capital ß is an official part of Unicode and it is now included in more and more typefaces. But type designers are unsure about how to draw this character. Here are some thoughts from a German type designer and reader on the different approaches … The Ligature Approach Not true! In German blackletter writing ß was understood as combination of long s (ſ) and z. We still call this character “Eszett” in German which just means “SZ”. So that’s the reason why many of the proposal shown above are drawn as an uppercase SZ ligature. And SZ was also the recommended replacement for ß in uppercase writing in the beginning of the 20th century. The dictionaries called this an interims solution to be used until a proper capital sharp S has been introduced. Over time, SS also became another replacement for ß in uppercase and by the end of the 20th century the original replacement with SZ was dropped and SS remained the only official writing according to the German orthography. Type designers are drawn to this ligature approach for the design of the uppercase ß, because it sounds like the most logical thing to do in terms of the history of the lowercase character. But I don’t think so. First of all: the history of the letter ß has yet to be fully explained. At this point we cannot be sure that it has definitely derived from a ſs or ſz ligature. And creating a new character based on assumptions alone, would not be a good idea. Secondly, the knowledge that ß has probably derived from a ligature is purely limited to typographers and graphic designers. Young German readers today don’t know a long s anymore and they don’t see the character ß as a ligature either. To them, it’s just a letter of the alphabet, just like any other letter. So they don’t expect an uppercase ß to look like a ligature. Letters are just conventions among the people who use them. They are “correct” when they are accepted by the users of this language—not because they are correct in a certain historical sense. And this is true for all Latin letters. We don’t draw an A so it looks like a Mediterranean ox head—we draw it the way, people are used to. In the same way, a capital ß should be designed according to the user’s expectations and not according to a possible, but still unclear history of the letter ß. It needs to work as a tool of communication and that is all that matters. A ligature approach using S and Z would certainly be possible, just like Æ and Œ are part of the Latin script. But I don’t think it would be desirable. It’s a forced design that doesn’t develop naturally. Even though some of the SZ ligature designs presented above look pretty nice, they feel more like stylistic ligatures for display use and I don’t see them as something Germans would want to use on a regular basis or for example in fine print or handwriting. Another popular idea among type designers is a design based on two S (see image above). But this is not an option at all! The whole point of having ß in the German alphabet today, is that it represents a different pronunciation than ss. An uppercase SS ligature will be understood as a stylistic ligature as you can see in this example: It represents “Professor” with a short vowel in front of the SS. So we can’t use a SS ligature as an uppercase representation of ß. The diacritical mark approach Diacritical marks are used frequently in languages which are written in the Latin script and in the old proposals for the capital ß several solutions are presented that use an S as the base glyph and added diacritical marks above, below or inside the letter. But a diacritical mark that is just used in the uppercase version and has a totally different counterpart in lowercase writing would be a very strange thing. German readers would only see it as a strange S, not as a capital ß and such a solution has little chance of getting accepted. The arbitrary shape approach Instead of using ligatures or diacritical marks the uppercase ß could also be based on arbitrary shapes. We could create a totally new character that would be in harmony with the design principles of the Latin script or we could borrow a design from a different language that isn’t used in German. But again: such solutions have little chance of getting accepted. The uppercase ß will hopefully be used more and more over the next couple of years and maybe even become an official norm. But if someone just uses an arbitrary shape today, it is very unlikely that Germans would agree to this design. The capitalized Eszett If you look at the capital sharp S designs that were introduced in the last couple of years, it is pretty obvious which approach is the most promising one. It is to start from the shape of the lowercase ß and turn it into a design that fits the uppercase letter. And that’s not a surprise: people in Germany and Austria often deal with the gap in their alphabet by simply using the lowercase ß inside uppercase writing. You can see that in Germany every day—from handwritten notes to TV ads. But the lowercase ß doesn’t belong into uppercase writing and the simple and obvious solution is to equip the German users with an uppercase Eszett that can easily be used and read, but looks also typographically correct in uppercase writing. And this is the solution I am also suggesting. The German readers don’t need to learn something new. They understand this letter instantly and the use of it solves all the common problems that result from the gap in the German alphabet. So how should this capitalized ß look like? There are now over a 100 designs done in this fashion and some work better than others. Here are a the two basic principles to design a capitalized ß: The left one is the most common design. The defining characteristics are the aperture on the bottom and the diagonal stroke on the top right side. The top left is usually done as a curve, but there are also designs where this part has been drawn as a corner or even with a serif. It also doesn’t hurt to make the capital ß wider than letters like B, but that is not a real requirement. The version on the right might fit in better with more calligraphic typefaces. The stem can even get a descender in italic version. Here are some examples of this approach which I consider successful: Note: The top right part is what makes this character unique! So make sure, you design this part in a unique way. The following example does not work for me … I just read it as a B, even though it has an aperture at the bottom. The top right part is what matters and it should never be rounded like a B. Make sure this curve is clearly broken by a diagonal stroke or even an inward S-like shape. So draw it either like this … or like this …

- 1 comment

-

- 1

-

-

- type design

- capital sharp s

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

The Capital ß design: Can we create an uppercase character from lowercase?

Ralf Herrmann posted a journal article in Journal

Today’s demand for a capital ß (“sharp s”) character is a functional demand. And a very simple one at that. It logically follows from two points: How the lowercase ß character is used today in the German alphabet How the Latin script works today as double-story alphabet Put these things together and it should be clear that the ß requires an uppercase counterpart like any other Latin character as well. So people still arguing against the capital ß will usually just ignore the functional aspects of it. They have to. Instead they typically argue in one of two ways: “because something in history …” or “because something is wrong with the design” The history of the character ß is an interesting topic. It might be one of the most interesting ones of all the Latin characters which developed over the last couple of centuries and I discussed what we know about this history in previous articles. But whatever you know (or think to know) about the history of the character—it cannot be a proper argument against a capital ß, because it has no influence on the two bullet points listed above. So it’s by definition irrelevant. And very often people arguing this way actually know very little about the history of the character. They just go by simple claims they picked up many years or even decades ago, which might not even be true or it might just be a tiny piece of the puzzle. But what about the design arguments against the capital ß? Now that the character is part of the official German orthography, the design argument seems to be the last straw for the “grumpy holdouts” in our field still rejecting the character. And of course it’s the most tricky aspect, since whether or not all or specific capital ß designs are successful is subjective. If someone likes or dislikes all or specific capital ß designs, everyone else might just want to respect that. It’s just an opinion and probably an honest description of a personal perception. But people might also argue for their opinion. They might try to give objective reasons why something is supposedly intrinsically wrong with the typical capital ß designs or even the idea of the capital ß itself. And those reason can and should be checked. Normally, the burden of proof would be on the ones making such claims. But unfortunately, after all these years debating the capital sharp s, not a single article has been written trying to make a convincing case against its design or existence. All we get is short social media posts with opinions and bold assertions. So let’s look at the reasoning we can gather from these posts against the capital sharp s design. Examples of modern capital sharp s designs: Scotch Modern, Goodchild Pro, Rooney Most capital sharp s designs today are based on a kind of “capitalized” ß, i.e. a design derived from the lowercase sharp s. That shouldn’t be a surprise. This design is instantly legible without requiring millions of readers to learn a completely new letter. At the same time it fixes the typographic problems one would create by putting the lowercase ß between capital letters as a work-around for the previously missing character. And this was and still is common practice. Even official documents like German passports did it this way to maintain the correct spelling of names in uppercase. But typographically, the ß character, like any lowercase character, isn’t meant to be put between uppercase characters. It might have a different height and it doesn’t use uppercase proportions. A capital sharp s based on a capitalized version of the ß can fix these problems. And so all functional and typographic problems are solved this way. Yet, some typographers, type or graphic designers insist, that this approach is somehow flawed and any capital sharp s created this way is intrinsically flawed because of it. In the most general way those people say: “You can’t create an uppercase character from a lowercase character.” But most of the time it is actually phrased this way: “You can’t create an uppercase character from a lowercase ligature”. Well, let’s look at those claims logically and one by one. The first one is based on the knowledge, that the (basic) set of Latin uppercase letters existed first. The lowercase letters came later and the claim essentially suggests, that this is the “natural order”, which can’t be reversed. The claim can be understood in two ways: either it talks just about the order of the development or about the designs that follow from that order. The order itself can hardly be used against the capital ß, because the same argument could also be used against the German umlauts (ä/ö/ü), which also existed as lowercase first. But no one really questions their existence, do they? But what about the design? Can we derive a proper uppercase shape from a lowercase character? Well, of course we can! Characters, not unlike words, are human-made cultural tools of communication. We create and shape them as we need them. And we have done this for thousands of years. If there is a functional demand for a word, we create it. If there is a functional demand for an uppercase letter, we can create it as well. The only reason this specific demand didn’t exist in the past was that German was mostly set in blackletter, which used mixed-case typesetting only. And since the ß never appears at the beginning of words, there simply was no demand for a capital version. Now this demand exists and and so now we create the letter. Plain and simple. But can we “reverse-engineer” the design process so to speak? And do we have to do that? Because one could argue, that the perfect capital ß would be one that could have existed 1000 or 2000 years ago and then later turned into the lowercase letter ß we use today. And people then argue, that the typical capital ß designs today are intrinsically flawed, because they don’t do that and just jump from lowercase to uppercase by “capitalizing” the lowercase shape. They basically say, that as long we can recognize the lowercase ß in there, it remains a lowercase letter and as a capital letter design is therefore flawed. So what about this argument? I fail to see any logic in it. It’s the reasoning you come up with while doing post-hoc rationalization. Because it just isn’t in line with reality. Again, we can look at the history of the German alphabet. German blackletter is full of (what we today consider) lowercase shapes turned into uppercase. Sachsenwald A blackletter H can be seen as the lowercase shape turned into an uppercase letter by changing the proportions and adjusting the design to fit the other uppercase letters. And that is exactly what is currently happening with the capital sharp s designs. But why do some consider this wrong for the capital ß, but they don’t complain about those blackletter shapes? If it happened in the past it is okay, if it happens today it is flawed? And to fully drive this point home, just consider this thought experiment: A type designer would have been shielded his or her whole life from seeing the Latin letter s/S. And then one day we show him or her the lowercase letter and ask the designer to create a proper uppercase version. What would the designer do? Well, we can’t know for sure, but it wouldn’t be surprising if the designers takes the letter skeleton of the lowercase s and enlarges it regarding its size and proportions to fit the other uppercase letters. The result could look exactly like our S looks today. But would this shape now be flawed because the lowercase character came first? Of course not! That would obviously be an absurd claim in this case. But it is the same claim people keep using against today’s uppercase ß designs. Today’s capital sharp s designs are nothing new by the way. As an example, this typeface from 1915 (“Koralle”) already used an uppercase design based on the lowercase design Visual similarities between a Latin uppercase letter and its lowercase counterpart aren’t a flaw—they are perfectly normal. Some character pairs (like S/s, as well as ones based on ligatures such as W/w) are very similar, others less so. But either way—it’s not a criteria for good or bad letter designs. The design of the S isn’t wrong, because it can be seen as a capitalized s. The blackletter H isn’t wrong because it looks like a capitalized h. And the capital ß isn’t wrong, because it looks like a capitalized ß. This is a logic in line with the reality of the Latin script. A good or bad letter design depends on the the skill of the type designer. Today’s Latin fonts need to work in both mixed-case and uppercase-only typesetting. That is the challenge for the type designer and with the capital sharp s being new, not all designs might be perfect yet. But logically, there is just no intrinsic flaw just because the lowercase letter came first. Simply knowing what came first, doesn’t affect how the readers perceive and read those letters. Now let’s move on to the ubiquitous ligature myth. Some people in our field seem to be unable to to see the letter ß as anything else than a ligature. And starting with that as a premise, they come to typical conclusions like: if it’s a ligature (like fi/fl) it’s not really a regular letter and there is no need for an uppercase version. We won’t address this in detail in this article. But the conclusion is wrong since the premise is factually wrong. Today, the sharp s cannot be grouped with typographic ligatures (like fi/fl). It anything, it would have to be grouped with character such as w and æ — regular characters historically probably derived from ligatures. But when type designers understand the ß as a ligature of two lowercase letter, they might think that an uppercase version needs to follow the same logic and so the uppercase ß must be created from the uppercase counterparts of whatever lowercase parts the ß is made of. And since there is supposedly a long s (ſ) in the ß design, some might conclude that a capital version cannot be created at all, since there is no capital ſ. Once more, I fail to see any good reasoning behind such claims. First of all, if you think the original lowercase parts of the ß matter and should be used for the uppercase version as well, which parts would those even be and how can you be sure to pick the right ones? Because at this point, there isn’t even scientific consensus about the origin of the ß. There is a single paper by Herbert E. Brekle, which can be considered scientific. But it mentions several possible sources. It might be one of those. It might be a combination. There might be other theories and sources that still need to be explored. Considering this status quo, it’s really surprising and disappointing how many designers and typographers claim to know what the ß was and therefore supposedly also “is”. (Which by the way is another logical fallacy.) But even if we would know for sure what the original parts of the ß are and if we happened to have those available in the uppercase alphabet: Would we need to create a new ligature from those individual uppercase letters? No! Case in point: We didn’t do that with the umlaut characters either. A German ä has definitely developed from merging lowercase a and e. When the uppercase versions were created much later, they didn’t use an Æ design to recreate the merger of a and e in uppercase as A and E. The type designers and writers of the time adopted the common design of the lowercase umlauts for the uppercase versions as well. At that time, that usually meant to put a lowercase(!) e on top of the uppercase letter. Not a very logical thing to do in terms of type history, but an understandable solution nevertheless. And one that isn’t questioned at all in hindsight. So why shouldn’t we be able to do that with the uppercase ß as well? And last but not least, there is another problem with the typical ligature arguments against the capital sharp s designs: It ignores the two historic branches of the German alphabet: blackletter and roman (or “Antiqua” as it is called in German). The sharp s was established when blackletter was the dominant type style in Germany. There is no doubt about that. But if we talk about the design of today’s typefaces, we hardly ever mean blackletter typefaces. We mean the roman designs. But it is a fact that the roman ß hasn’t developed from a ligature. It hasn’t developed at all. It was introduced by a committee as a new character with a new design at the beginning of the 20th century. The ß design as introduced and used in the early 20th century. The left part does indeed look like a long s (ſ), but that special character had already been removed from the roman orthography of the German language at that point. And the right part was neither a roman s, nor a roman z. So calling it a ligature actually makes little sense. If anything, it hints at a ligature design. It didn’t develop from a ligature, nor did the “parts” even exist individually in the orthography they were used in. What was created was a single roman letter with its own unique design. And that by the way is how the vast majority of people in Germany and Austria perceive it. They don’t see a ligature in the character w and they don’t see one in the character ß. It’s one design in both cases. So if we talk about the design for the roman capital ß, what else should it be based on than the lowercase ß? Why go further back than its introduction at the beginning of the 20th century? Why go by our sketchy knowledge about blackletter predecessors? In today’s roman typefaces, we hardly ever draw any German character (ß, ä/Ä, ö/Ö, ü/Ü) the way they looked in blackletter. So why would the capital ß—as the only exception—have to be based on asserted historic lowercase parts in blackletter put together again as uppercase ligature? It’s just not conclusive and the logical fallacy of special pleading. In conclusion: if some people don’t like an uppercase ß that reminds them of the lowercase ß, so be it. But I can’t see how you can make a case, that this would be an objective flaw of such designs. If the existing uppercase characters are allowed to have similarities to their lowercase counterparts, so does the capital ß. Insisting that a capital sharp s with similarities to the lowercase ß remains a lowercase letter or ligature because of those similarities—even though it was specifically drawn as uppercase letter with uppercase proportions—is frankly an absurd claim because it is not in line with the reality of the Latin script. And the assumption, that the ß character developed from a ligature also doesn’t change anything in that regard. If you accept German umlaut characters not to be drawn from their historic parts, then logically you should accept the same for the uppercase ß. The Latin script has a history spanning over thousands of years and characters were added all the time. There is nothing special about the current change of adding a capital sharp s. In the future and in hindsight, neither this change nor the design will be questioned. Just because this single change out of the hundreds of changes happens in the present and is in conflict with the typesetting conventions one grew up with, doesn’t mean that it is flawed. Sure, a new character might briefly stand out because it is new. But that doesn’t mean there is something wrong with the design. In the end, it’s all in the hands of today’s type designers. We know they can draw a coherent set of over 100 Latin characters and all sorts of optional ligatures—nothing is stopping them to make their capital sharp s designs work just like any other Latin character. -

Languages which use letters based on the latin alphabet are set in two separate alphabets: uppercase and lowercase. We set text usually either in mixed-case or in uppercase/small cap letters. At any time we can switch between the two without touching the content of the text. This however, is not possible in Germany and Austria where the lowercase alphabet consists of 30 letters (Basic latin + ä, ö, ü, ß), but the uppercase alphabet has just 29 letters (Basic latin + Ä, Ö, Ü). How did this happen? Well, Until the 1940s German was usually set in blackletter and such texts were never set in uppercase, because of the wide and decorated design of these uppercase letters. And since there is also not a single word that starts with an ß (Eszett), there was simply no need to have an uppercase version. But this has turned around. Today, we hardly set German text or names in blackletter and the use of uppercase/small caps is still popular for various reasons. So there is an obvious gap in the German alphabet. A design for a capital Eszett by the font foundry “Schelter & Giesecke” (Hauptprobe 1912) The existence of this gap was acknowledged a long time ago. In 1903 a commission of German, Austrian and Swiss printers and font foundries announced that the letter ß should also be included in any non-blackletter typefaces. A capital version was also discussed but the commission could not agree on one design at this time. So it became common practice to replace the letter ß with SS or SZ in uppercase text. This however was never meant as a real solution to this problem. In 1919 the Duden (a German orthography book) explained: “The use of two letters for one phoneme is just an interims solution, that must be stopped, once a proper letter for the capital ß has been designed.” (Original quote: „Die Verwendung zweier Buchstaben für einen Laut ist nur ein Notbehelf, der aufhören muß, sobald ein geeigneter Druckbuchstabe für das große ß geschaffen ist.“) During the 20. century a capital Eszett appeared occasionally as you can see in these examples here, but the topic couldn’t reach a broader audience. Capital Eszett on a German orthography book from 1965 A novel using a Capital Eszett, printed in 1971 So the interim solution of replacing ß with SS is still in use today. Germans are used to this practise but it constantly causes trouble. Here are the two main problems: Proper names Depending on where you live in Germany or Austria the letter ß is quite frequent in the names of cities or families (see illustration). In Germany there are 444 cities that use an Eszett. According to a rough estimation around 2 million people have to use an Eszett when they should write down their address. But how do you do that, when the form of the postal service asks you to write in uppercase only? Sure, one can replace the Eszett with SS, but unfortunately this is a one-way street. Once the name has been converted to uppercase it cannot be converted back to mixed-case letters, because it is then unknown if the name WEISS actually stands for Weiß or Weiss. Both names exist and this is true for almost all names with an Eszett. This is a real problem in today’s electronic data processing. When people enter their address in web forms they might do it in mixed-case, uppercase and lowercase letters. This can be fixed with methods of case folding, but when SS is used as a replacement for an Eszett this will not work properly. And beside these technical problems, the spelling of proper names is something that you shouln’t toy with. My first name for example, exists as Ralf and Ralph in German. Of course, I accept only one spelling. Imagine, my name would be Ralf Herrmann in mixed-case texts and RALPH HERRMANN in uppercase! Sounds absurd? Well, this is exactly what we do to people who have an Eszett in their name. Both Mr. Meißner and Mr. Meissner will be set as MEISSNER in uppercase. And so far, almost everyone I have talked to, who has an Eszett in the family name, hates such a replacement. Lowercase ß in uppercase text The same is true for city names. I come from a small town called Pößneck. The Eszett is part of the identity of the inhabitants and the spelling PÖSSNECK always causes heated debates. They rather use the lowercase letter between the uppercase letters: PÖßNECK. But this is of course a typographic nightmare. Pronunciation In 1996 the German orthography was changed and this also affected the use of the Eszett. Now the use of Eszett vs. double-s clearly points out if the vowel in front of the s-like sound should be spoken short or long. The ß in Fuß (foot) means long vowel – The ss in Kuss (kiss) means short vowel. As nice and simple as this rules is, it will certainly cause problems when uppercase text is used and the Eszett will be replaced with SS. Now Fuß becomes FUSS and this would require a different pronunciation, just because it is set in uppercase text! And it gets worse: there are common words like Masse (weight) and Maße (measures) which both become MASSE in uppercase texts. Conclusion As one can clearly see: replacing one character with two other characters just because the case of the text changes, doesn’t make much sense and causes serious problems. The simple and logical solution is to complete the alphabet, so there is a counterpart for every letter in uppercase and lowercase text. Anyone who cares about type and language should agree to this simple solution. And yet, there are some typical counter-arguments I always hear, when I talk to professional designers or typographers. Which is rather suprising! Those people, above all, should understand how the two alphabets in Western languages should work properly together. But anyway, here are the counter-arguments: There can’t be an uppercase form of the Eszett because it is actually a ligature! A really pointless argument. The term ligature just means that there is something connected in this letter. It doesn’t say anything about the purpose of the letter. Sure, we don’t need an uppercase fi-ligature, because the connection of “f” and “i” only serves a purpose in lowercase text, but as I have shown above, the Eszett is distinct letter of the alphabet in German and Austria with a specific function concerning the pronunciation of words. Just like the ligature W—which was formed from two V—has a distinct phonetic function. There can’t be an uppercase Eszett because the Eszett contains a long-s, which doesn’t exist as uppercase letter! Again, pointless! Letters are abstract symbols for anything we assign to it. This in everything that matters and we cannot divide letters into “right” or “wrong”, because of their history or the origin of certain letter parts. Or is the letter S wrong because it doesn’t look like a Phoenician tooth anymore? Letters, just like words, are tools of communication. They can change their structure and meaning and they can be invented whenever there is need for new tool at a certain time. Concerning the uppercase Eszett, this need was created when Germans stopped using blackletter and it is about time to fulfill this need. In a globalized society, the letter Eszett only causes trouble. We should stop using it. Before the uppercase Eszett became part of Unicode (where it is called Capital Sharp S), I was also sceptical about its use. Putting an non-standard character in digital documents will certainly cause problems. But since 2008 it is part of Unicode and this is the Lingua Franca of the modern world. It can be used on any device anywhere on the planet. There is now no need to omit any character of any language anymore. It also doesn’t prove anything that Switzerland is doing fine without an Eszett in their Alphabet. This character has a distinct function that millions have learned and it is written in millions of books. And while this is the case, there is no real point to remove it from the alphabet. A capital Eszett for the Bauhaus University Weimar The capital Eszett today While all attempts to introduce an uppercase Eszett during the 20. century failed, now all signals are go for it. The topic appeared in 2003 on my typographic website Typografie.info and quickly spread all over the German-speaking internet. And it hasn’t stopped since. The introduction of the uppercase Eszett in the Unicode specification allowed the instant use of this character. This is something that could hardly be done in the time of metal type. Nicely integrated into the Corporate Design The capital Eszett is now used more every day. It is included in several Windows 7 fonts and more and more type designers are designing a capital Eszett for newly released typefaces. I would like to finish with a quote about the capital Eszett from 1879, which I consider as true today as it was then: “Indeed—it is a new character; but maybe this newness is the only thing you can hold against it.” (Original quote: „Allerdings – es ist ein neues Zeichen; vielleicht ist aber die Neuheit das Einzige, was sich dagegen vorbringen lässt.“)

-

- capital sharp s

- eszett

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with: